Originally developed to meet the needs of biologists, the technique of conservation called freeze-drying - technically known as 'lyophilisation' – was for a long time confined to research labs specializing in pharmaceuticals. It was only after the First World War that it was applied on a large scale to the preservation of everyday foodstuffs.

In 1811 the Scottish

mathematician and physicist John Leslie was the first person to change water

vapor into ice directly-that is, without passing through a liquid stage in

between. Two years later the chemist William Wollaston demonstrated the same

process to the Royal Society in London. It did not occur to either of them that

this effect might one day be used for the preservation of food.

Almost a century later, on 22 October 1906, Arsène d’Arsonval presented a research paper to the Academy of Sciences in Paris entitled 'On distillation and desiccation in a vacuum by means of low temperatures'. Written with the help of an assistant, F Bordas, in the biophysics laboratory that D'Arsonval ran, the paper addressed the subject.

That was preoccupying many biologists at the time: how to preserve

samples of tissue, serum, germs, and other substances used in research.

D’Arsonval had devised a technique of freeze-drying. Three years later an

American, Leon Shackell, rediscovered the process and developed it.

Stages in The Process

Freeze-drying involves

three stages. First, the sample is frozen solid. Second, it is subjected to

sublimation – a process that transforms a solid into a vapor without going

through a liquid phase. By this stage, the sample has lost most of its water

through evaporation, with no heat involved. Finally, to rid the sample of any

residual water, it undergoes a secondary desiccation process, in which the

temperature is raised slightly, although still usually staying below zero.

The end product is

almost totally dehydrated but retains structure and color. Crucially, many of

the biological functions recover once the sample is rehydrated since

freeze-drying does not damage the molecular structure or cell tissue. Neither

ordinary drying nor freezing alone produce such a satisfactory result.

Impact of the War

Because of its cost

and complexity, freeze-drying was long restricted to scientific laboratories.

This changed in the 1930s. With another world war looming, there was an urgent

need to be able to stockpile large, transportable quantities of blood plasma

for transfusions to casualties.

From 1935, the

American Earl W Flosdorf published the results of his efforts to freeze-dry

human blood serum and plasma for clinical use. The desiccation of blood plasma

from a frozen state, performed by the American Red Cross for the US armed

forces, was the first extensive use of freeze-drying.

Flosdorf, together

with researchers in Britain under Ronald Greaves, pioneered large-scale

commercial freeze-drying of foodstuffs at this time. Meanwhile, Ernst Boris

Chain, the co-discoverer of penicillin, initiated the lyophilisation of

antibiotics and other sensitive biochemical products.

From Drugs to

Freeze-dried Coffee

At the end of the war,

the pharmaceutical and cosmetics industries adopted freeze-drying for vaccines,

drugs, and other preparations. Freeze-dried coffee, which had been brought to

Europe by American GIs, helped to stimulate the freeze-drying of foods.

At first, because the

process was still very costly, it was only used for luxury items. But before

long freeze-dried soups, spices and even entire prepared meals appeared in

packets on grocers’ shelves. In the 1960s NASA adopted freeze-dried meals for

astronauts on its space programmed.

PROS AND CONS

Most micro-organisms

need water to survive and grow; provide almost the same nutritional value as

fresh versions. The main freeze-drying is very effective at the disadvantage of

freeze-drying is it preventing the growth of microbes and inhibiting harmful

chemical relatively high cost, which has hampered the full development of the

technique even to the present day. reactions.

The use of

freeze-dried products in the Second World War Also, while freeze-drying

commodities demonstrated the huge benefits, they such as coffee and tea, which

have no offer in storage and distribution. If cell structure, is successful and

cost-effective, other products do not fare so well.

It is especially hard

to properly freeze-dried, most foods, either raw or cooked, have a long shelf

life even at room temperature sublimate all the water vapor from foods with

abundant cell membranes and can be reconstituted simply by adding water; the

resulting in products like meat, vegetables, and fruit.

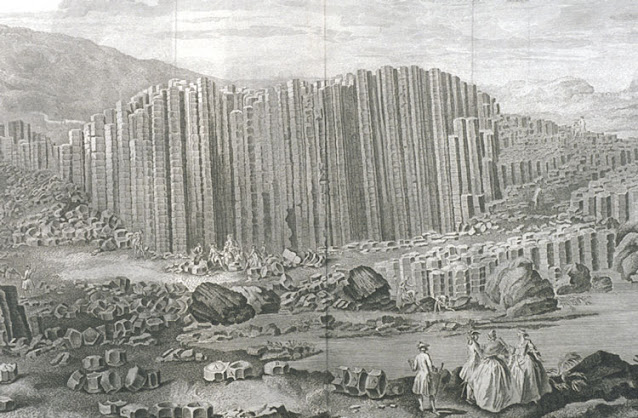

INCA KNOW-HOW

Father José d'Acosta, a Spanish Jesuit priest I on a mission in Peru, reported in 1591 that the Incas conserved food crops by carrying them up into the Andes above Machu Picchu. There, the combined effects of the cold, the Sun, and the relatively low atmospheric pressure at high altitudes caused the water in the food to sublimate. The resulting products, which the Incas called charqui (dried meat) or chuno (dried potatoes), were the earliest known freeze-dried foods.